SELECTED EXAMPLES OF OUR COLLABORATIVE WORK

Our work to date is rooted in building trust and relationships and collaborating with residents, community stakeholders, and local policymakers. Listening to the history of a community and having honest discussions about the growing inequities and threats that are facing too many communities. Utilizing our expertise in both policy and practice but never forgetting the importance of people.

The majority of our work has been made possible through the support of the Center of Community Progress and below represents just a few selected examples of our collaborative work with communities across the country.

Puerto Rico

For several years now, Frank and Kim have been on the ground working with a group of incredible volunteers that really kicked into high gear after Hurricane Maria. The storm further uncovered the entrenched systemic challenges associated with vacant and abandoned properties across the island. Helping to build capacity on the ground was the first priority and resulted in the creation of the Center for Habitat Reconstruction. This nonprofit has led the rethinking of eligible uses of CDBG-DR funding to engage the residents that have been most impacted by disaster. Community land bank legislation was drafted and passed and several communities have moved forward with creating a land bank to acquire vacant nuisance property and support community control of land for affordable housing and other local goals. Over the course of 2022 and 2023 we have worked with Luis Gallardo and the Centro para la Reconstrucción del Hábitat (CRH) in creating a

Spanish translation of LAND BANKS AND LAND BANKING (2nd ed. 2015). This translation, BANCOS DE TIERRAS Y EL MANEGO DE SU TENENCIA (2022) was published in the fall of 2022 and available on this website under the “Our Publications” tab. For further information on the CRH and its work in Puerto Rico, see www.crhpr.org or contact Luis Gallardo at gallardo@crhpr.org.

Alabama

Beginning in 2021 Frank and Kim have worked with key stakeholders from Birmingham, Mobile, and Montgomery. One specific focus has been on improving the state’s land bank legislation so land banks will have the requisite powers to be more effective and equitable in acquiring vacant property, and to be able to serve as a critical partner in times of climate change disasters. At the end of the 2022 Alabama Legislative Session Senate Bill 339 was initially introduced. It was reintroduced in the 2023 legislative session as Senate Bill 6. This legislation has now been significantly revised and strengthen in anticipation of its reintroduction in the 2024 legislative session.

Georgia

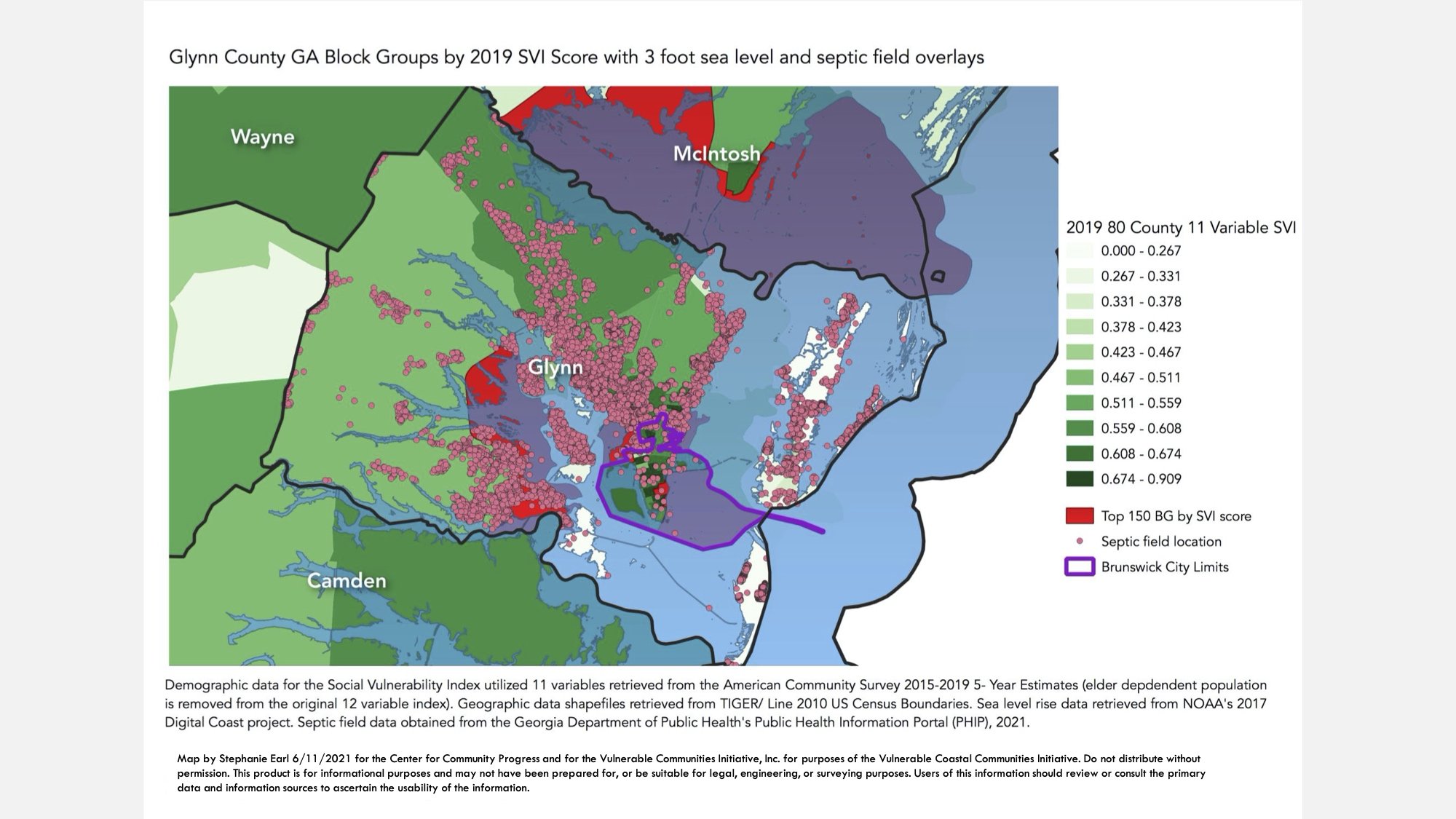

The initial research in 2021 by Stephanie, Jazz, and Frank focused heavily on the five Georgia coastal counties: Camden, Glynn, McIntosh, Liberty, Bryan, and Chatham. The key approaches, the data analyzed, and the maps created are all summarized in the following section, Our Research. In the summer of 2022 we collaborated with the Center for Community Progress in extensive research followed by meetings in Glynn County (Brunswick) and MacIntosh County, Georgia focused on land banks and land banking, on disaster resiliency planning, and on the needs of specific neighborhoods. During 2023 we have focused more deeply on learning from, and collaborating with the Glynn County-Brunswick Land Bank Authority and supporting it in the development of new policies and procedures.

Tennessee

In early 2023 we began work once again in Memphis and Shelby County, Tennessee. Building on earlier work we did in Memphis in collaboration with the Cecil C. Humphreys School of Law at the University of Memphis and its Neighborhood Preservation Clinic we are also working The Works, Inc. in evaluating existing code enforcement, property tax enforcement, and land banking initiatives.

Disaster Relief

In order to listen, to learn, and to serve, Frank serves with a Disaster Early Response Team (ERT), coordinated by United Methodist Church Committee on Relief (UMCOR. In 2022 and 2023 this has involved service in eastern Kentucky following the catastrophic rains and flooding in eastern Kentucky in late July, 2022, in Port Charlotte, FL following Hurricane Ian in October, 2022, and in Griffin, GA following tornados in January, 2023.

OUR RESEARCH

VCCI began with a focus on five southeastern states which border the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean: Alabama, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina. This selection of communities from Mobile to Norfolk was made in part because of proximity to sea level rise and coastal flooding, and in part because of common elements in social and legal history. The decision was made to exclude Norfolk, Virginia because of the unique issues presented by the naval base and federal properties, and to exclude Mississippi and Louisiana because of the unique issues presented by the Mississippi Delta.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Digital Coast study conducted in 2017 included 88 coastal counties in our five states, which we adopted for our study area. The utility of matching the NOAA study area is that it permits an analysis of sea level inundation at varying levels of projected sea level rise. In light of the impacts of recent hurricanes on slightly inland counties, we added three countries to the NOAA list (Leon County, Florida; Calhoun County, FL; Lenoir County, NC) for a study area of 91 counties. After reviewing the dominance of the most vulnerable block groups in highly populated Florida counties, the decision was made to exclude those counties that have population above 450,000 and a population density above 470 persons per mile, due to our desire to identify block groups in rural areas with insufficient municipal resources. The result was the exclusion of Brevard, Broward, Duval, Hillsborough, Lee, Miami-Dade, Palm Beach, Pasco, Pinellas and Volusia counties in Florida. We also elected to exclude Monroe County, FL (the Florida Keys) on the basis that its social and climate vulnerability issues are sui generis. The final 80 county study area counties by state are as follows: Alabama 2; Florida 30; Georgia 10; South Carolina 12; and North Carolina 26.

In order to create maximum specificity as to the geographic location of vulnerable communities, we utilized the 2014-2018 American Community Survey (ACS) 5-year estimates at the block group level. In the 80 county study area there are a total of 5011 block groups. We began VCCI by exploring vulnerability with reference to the broad categories of social and economic characteristics. To quantify social vulnerability empirically, we began with the Center for Disease Control’s (CDC) social vulnerability index, which consists of 14 variables related to housing, poverty, race and transportation developed in the context of disaster management. Of the CDC index variables, we excluded four: per capita income, percent in multiunit housing, percent overcrowded, and percent in group quarters. We included the remaining 10 CDC variables and added two of our own: percent renters and percent housing-cost burdened. Data for the twelve variables were retrieved at the block group level from the American Community Survey 2014-2018 5- Year Estimates for our study area counties. While the CDC’s index is calculated at the tract level, we chose to use the block group level for more specificity. We elected to give equal weight to each of the 12 variables in creating the index score and to rank relative vulnerability for each geography in reference to the full study area, following the CDC’s model. In analyzing the 12 variables, both regression analyses and correlation analyses were run. In the original index, all of the variables made statistically significant contributions to the index score except for the percent of the population over 65 years old and the percent in mobile homes. Iterations of the index excluding those two variables have also been conducted. The decision was made to permanently exclude the elder dependent population variable from our index, as the “retiree effect” of a large non-vulnerable elder population skewed our results.

Using our 11 Variable VCCI social vulnerability index, we ranked and mapped all of the block groups in the study area. We then ranked and mapped 150 block groups with the highest social vulnerability index scores in our 80 county/5011 block group study area.

The second step of our research was to correlate social vulnerability with climate change vulnerability The basic data set for coastal climate change vulnerability is the NOAA Office of Coastal Management 2017 Digital Coast data. Files are available from the Digital Coast study which demonstrate inundation by sea level rise scenarios from 1 foot to 10 feet. An example of the NOAA data for a three-foot rise in sea level over our social vulnerability index was created;

Of our 5011 total block groups, 540 have their centroid within the water line for three foot sea level rise. We did separate analysis of only these 540 block groups ranked with our 11 variable Social Vulnerability Index. We hope to add a flooding model as well to capture climate risk beyond sea level rise. Using the combination of both social vulnerability and climate change vulnerability, and then ranking the top 150 blocks groups, has identified locations in 45 counties in our study area: Alabama (2 counties, 9 block groups), Florida (17 counties, 44 block groups), Georgia (6 counties, 21 block groups), North Carolina (14 counties, 40 block groups), South Carolina (6 counties, 36 block groups). Another interactive data and mapping tool is the Surging Seas Sea Level Rise Analysis available from Climate Central. This resource permits a high degree of geographic specificity, adjustments across a broad range of social vulnerability variables, and includes not just sea level rise but also coastal flooding. As we correlate climate change vulnerability with the VCCI social vulnerability index we anticipate also examining the available data on FEMA claims8 and on NFIP claims. The FEMA data is available at the census tract level, but the NFIP data is only at the state level. We also hope to be able to obtain data for and map, in as small a geography as possible, the location of repetitive loss payments under federal programs. We have also expanded our data overlap analysis to include data on inland flooding, septic and other onsite wastewater management systems, publicly subsidized housing, and land tenure characteristics.

Our work in Phase I of VCCI – identifying vulnerable communities by both social vulnerability and by climate vulnerability, is a dynamic rather than a static process. We will continue this analysis by adding new data sources and by constantly updating our current data sets. The primary focus at this time has been the identification of the 150 most vulnerable block groups as determined both by social vulnerability and by climate vulnerability. By way of example, we have created two maps that depict at the county level (Glynn County, Georgia) the overlay of block group social vulnerability index scores and 3 foot sea level rise.

Acquiring, analyzing, and mapping key data sets is a dynamic and iterative process. We learned in 2021 that one of the most pressing issues confront rural communities, particularly those facing climate change, is the absence of effective on-site waste water management systems (septic systems), which is compounded by the lack of regulatory oversight and fundamental data on the locations of any and all such systems. Key initial research undertaken by Courtney Melissa Balling, a graduate student at the University of Georgia allowed us to map the locations of known septic systems with the locations of our doubly vulnerable communities.